History also tells us that war eventually consumes even the most skilled players. Netanyahu, for all his maneuvering, cannot outlast the rage of a public that will demand answers when the dust settles.

I was sitting with my wife in a restaurant, celebrating her early retirement from a miserable job and the beginning of a new adventure.

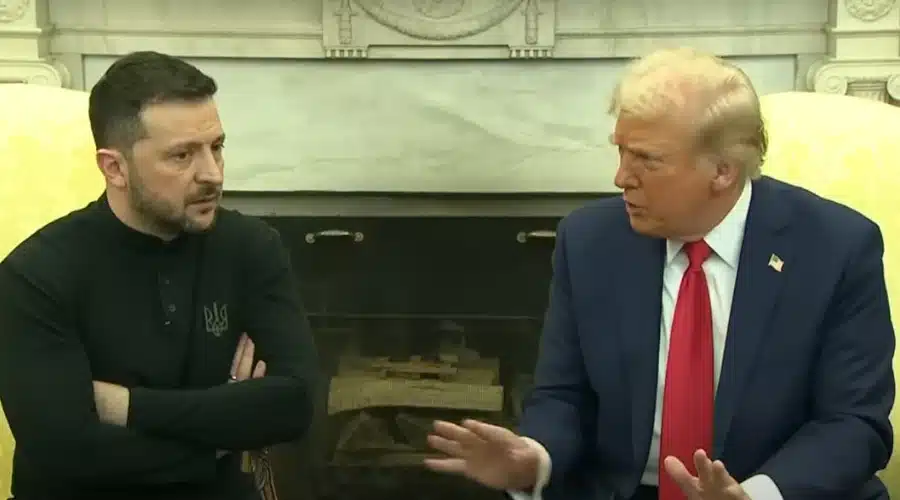

My phone buzzed in my pocket. A message lit up the screen: “Are you watching this shit?” There was a link to the Trump, Zelensky, and Vance press conference.

Like everyone else, I was fascinated by this circus. It triggered me to think—what is it about war, about conflict, that so often becomes the lifeline of a leader?

Not just the obvious wars—tanks, missiles, charred landscapes—but the ones fought in conference rooms, in media headlines, in the manufactured crises that keep the right men in power at the wrong time. War as an existential necessity, not just for nations but for the men who stand at the podium, fists clenched, voices raised, promising that the enemy—whoever they declare it to be—is the singular reason they must remain in power.

I always love to hate that about Churchill, a man who thundered through history with defiance, an unwavering resilience. War was his crucible. Without it, what was he? A relic. The moment peace settled in, the people who had cheered him through bomb raids and victory speeches shoved him aside for a quieter, more palatable future.

Thatcher knew it too—before the Falklands War, she was floundering, and near her expiry date. Then came Argentina's invasion, the perfect battlefield for her iron conviction. She crushed them, and in doing so, resurrected herself.

Caesar is another case in point. He understood that power does not reside in the mere ability to govern, but in the capacity to wage war. He went to Gaul not just to expand Rome, but to carve himself into its soul. Victory brought riches, loyalty, a sword sharpened against the necks of his political enemies. He crossed the Rubicon not because he had to, but because peace would have dismantled him. He had become war incarnate, and when it left him, so did everything else.

Fast forward to Zelensky in his fatigues, transforming overnight from a comedian and an actor to commander-in-chief. The world fell in love with him. The West adorned him with standing ovations, weapons, and billions in aid, seeing in him the embodiment of resistance.

But here’s the question that lingers, the one that no one wants to say too loudly—what happens when the war ends? What is Zelensky without the fight? His authority, his moral clarity, all hinge on the war continuing. In fairness, to negotiate would mean to compromise. And to compromise would mean a reckoning. He does not have that luxury. So, the war must go on.

Netanyahu plays a different game, but the rules are the same. He is a creature of conflict, a leader who has survived not despite war, but because of it. The October 7th attacks were his crucible, the moment his career should have shattered under the weight of failure. But he did what he has always done—he turned disaster into a mandate. War became his refuge. As long as Israel is fighting, Netanyahu remains necessary. The moment the guns go silent, the moment the questions start rolling in—how did this happen on his watch?—the illusion shatters. And so, the war must go on.

Then there's Trump. The self-proclaimed "peace-time" president who, paradoxically, thrives on perpetual war of not tanks and bombs but of mind games waged in headlines, in trade deals, in the relentless hammering of “us vs. them." He did not need a battlefield to construct his war; he built one wherever he stood. China, the deep state, the media, the establishment, the swamp—he fought them all, not to win, but to keep fighting, because without his geopolitical wars, Trump ceases to exist. The moment the battlefield disappears, so does his relevance. He is not a peacemaker. How could he be when he talks about taking Greenland? When he talks about taking the Panama Canal? When he talks about turning Canada into the 51st state. He is a warlord of a different breed.

And this is the truth that lingers behind every leader who has ever stood at the precipice of history: war is not always something that happens to them. Sometimes, they need it. Sometimes, they crave it. Because war forgives sins. War rewrites failures. War turns the weak into the indispensable and the floundering into the steadfast.

Would Zelensky still be in power if Ukraine had never been invaded? Would Netanyahu have survived this long without a perpetual state of conflict? Would Trump be relevant if he weren't always at a war of words with something?

These are not comfortable questions, but history rarely offers comfortable truths. Leaders and war exist in symbiosis, feeding off each other. And the people? The ones who fight, who suffer, who die? They are the cheap currency with which legacies are purchased.

Look at Napoleon, a man who needed war as much as war needed him. His empire was not built on diplomacy but on conquest, a perpetual machine of battle that sustained his legend. Victory cemented his rule. Defeat destroyed him. There was no middle ground. No exit strategy. He had to keep marching forward because the moment he stopped, he was no longer Napoleon. His exile was not just geographical; it was existential. He had ceased to be relevant.

And yet, history also tells us that war eventually consumes even the most skilled players. Netanyahu, for all his maneuvering, cannot outlast the rage of a public that will demand answers when the dust settles.

Zelensky, even if victorious [which is doubtful with Trump in power], will have to navigate a post-war Ukraine riddled with scars, political fractures, and Western expectations.

And Trump—his war, the one he thrives on, has always been with himself, his own need to fight, to win, to never be irrelevant. But there comes a day when even the best provocateurs run out of battles worth fighting.

After I read the text message, I glanced back at my wife, sipping her wine, relaxed, free from the battles she had fought in a job that had drained her. She had escaped her war. Most people don't get that luxury. Because out there, somewhere, a leader is crafting their next battlefield, their next justification, their next reason why the fight must continue. Because for them, peace spells the end. And power is everything.

But power, like war, is never truly won—it is borrowed. And when history comes to collect, it does so with brutal efficiency. The leaders who could not let go of war eventually become its casualties.

This phenomenon—the symbiotic relationship between leaders and conflict—manifests uniquely across different types of warfare. For some, like Churchill, it is the existential threat that transforms them from politicians to saviors. For Thatcher, war offered redemption, a chance to redefine her leadership through decisive action rather than controversial domestic policies.

Caesar represents another variation—the leader who uses military conquest as currency in the political marketplace, accumulating power through battlefield victories that translate into influence at home. His story illuminates how war becomes not just a tool but an identity, inseparable from the man himself.

These historical figures demonstrate a critical pattern: the more a leader’s identity becomes intertwined with conflict, the more difficult the transition to peace becomes. Churchill's electoral defeat following World War II wasn't merely political—it was the inevitable consequence of a wartime identity struggling to find purpose in peacetime governance.

Modern leaders exhibit these dynamics in evolved forms. Zelensky's transformation doesn't simply mirror Churchill's wartime leadership; it reveals how contemporary media amplifies the heroic wartime narrative, creating a global persona that would be impossible to maintain in ordinary political circumstances. His dilemma extends beyond political survival—it's about preserving a moral authority that might dissolve with compromise.

Netanyahu's relationship with conflict operates through different mechanisms. Unlike Churchill facing an existential threat or Caesar seeking conquest, Netanyahu has mastered the perpetual crisis—neither allowing conflict to end nor letting it escalate beyond control. This represents a modern adaptation of war leadership: maintaining the perpetual emergency that justifies extraordinary measures without resolution.

Trump's innovation lies in detaching warfare from physical battlefields entirely. By waging rhetorical wars against institutions, individuals, and ideologies, he created the emotional benefits of wartime leadership—unity among supporters, clarity of enemies, suspension of normal judgment—without military action. His approach shows how the psychological components of conflict can be extracted and deployed politically even in nominal peacetime.

Each of these leaders demonstrates a different facet of the war-leadership relationship. Some need the validation of military victory, others require the distraction from domestic failures, and still others depend on the narrative clarity that conflict provides. What unites them is not simply a need for war, but a relationship with conflict that serves specific functions in their leadership.

The ultimate tragedy lies not in their individual fates but in the collective cost. War, whether literal or metaphorical, demands sacrifice—not primarily from leaders, but from citizens drawn into conflicts that serve political necessities rather than national interests. The real currency of these conflicts isn't measured in territorial gains or political outcomes, but in human lives caught in the machinery of leadership ambition.

Perhaps the most sobering lesson is how this pattern persists despite our historical awareness of it. We recognize the phenomenon—leaders who need enemies, who thrive in crisis, who struggle to govern without conflict—yet repeatedly find ourselves swept into their narratives, cheering the very performances that perpetuate cycles of unnecessary confrontation.

As I watched my wife enjoying her hard-earned peace, I wondered about our collective complicity in this cycle. How many of us willingly participate in manufactured conflicts that serve purposes beyond our understanding? How many wars—political, cultural, economic—do we fight because someone else needs us to?

Further Reading

For readers interested in exploring these ideas further, my analysis draws on reporting and research from:

Historical Context:

Machiavelli's The Prince on war as a ruler's duty

Historical accounts of Churchill's post-war electoral defeat

Documentation of how the Falklands War revitalized Thatcher's career

Historical analyses of Caesar's use of the Gallic Wars for political advancement

Contemporary Leadership:

Reuters reporting on Zelensky's wartime presidency and approval ratings

The Kyiv Independent's coverage of criticisms of Zelensky's war stance

Reuters analyses of Netanyahu's political survival strategy and legal troubles

Chatham House research on Netanyahu's "total victory" approach to Gaza

Reporting on Trump's claims of being a "peace-time president" while engaging in economic and rhetorical warfare