We've been taught in school that first came the Agricultural Revolution, then the Industrial one, followed by the Digital, and now we talk about the AI revolution. But the fact is that revolutions didn't happen in series, but rather in parallel, each enriching and evolving the other. With Trump's new tariffs, we're not witnessing a new revolution but rather the creation of a new relationship between the revolutions.

I'm amazed at the laconic reaction by business leaders and politicians around the world to the new announcement, as it's not new at all. Trump has been talking about it for the past two years. And what have you done to prepare for it? Well, nothing. This reminds me of Britain leaving the EU. There are still people crying over it. Why? It's not about crying but rather about monetising. Get over yourself and start creating.

And here lies the truth: the economic dependency on the US is clearer than ever now, especially in the EU. Instead of using the time before the tariffs to create an ecosystem of intellect, one that can produce IP and innovation that reimagines the revolution, you did nothing. So, you cry now! I'm not against or for tariffs; I do not care. I'm for moving forward, creating, inventing, and innovating. There is an opportunity to rethink automation, manufacturing, the logistical ecosystem. Use this as well.

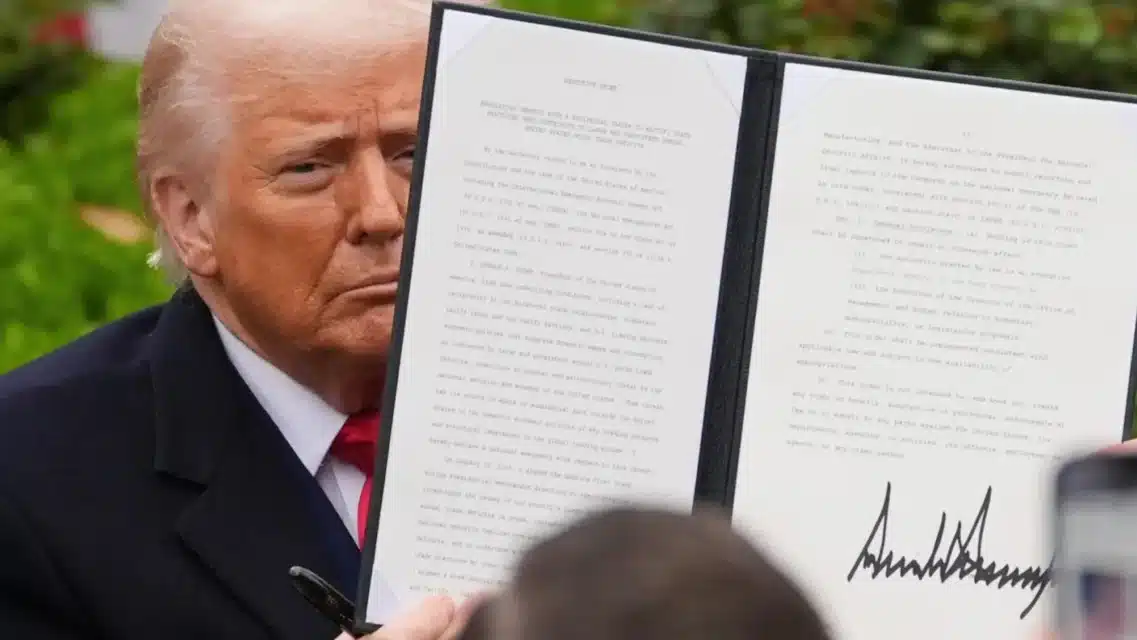

The 10% bombshell: déjà vu for the wilfully obtuse

Good heavens, the pearl-clutching! You'd think Trump just invented tariffs rather than resurrecting one of the oldest economic tools in history. His April 2, 2025, announcement of a blanket 10% import tax—with eye-watering surcharges for the special offenders—has sent the global economic establishment into apoplexy. Markets tumbling, economists prophesying doom, diplomats drafting strongly worded letters… all utterly predictable.

Let's be clear: this isn't revolutionary—it's reactionary in the most literal sense. Trump is channelling 19th century economic nationalism in a 21st century globalised economy. It's Smoot-Hawley meets TikTok, mercantilism for the digital age. The world hasn't seen protectionism of this magnitude since before World War II, yet anyone genuinely surprised by this announcement has been living under a rock (or perhaps in a Brussels bureaucrat's bubble).

When Trump thunders about America being “looted and pillaged” by foreign nations, he's performing a script as old as human civilisation. The Romans did it, the British Empire perfected it, and now America takes its turn at economic territorialism. The only difference is the scale—globalisation has made the interconnections deeper, the potential disruption more severe.

Global supply chains: sitting ducks on borrowed time

If you've spent decades building a business model entirely dependent on cheap Vietnamese labour, Chinese components, or Thai assembly, what on earth made you think this arrangement was sacrosanct? Did you imagine the global trading system established after WWII was divinely ordained rather than a political construct that could change?

The targeted surcharges tell their own story: Vietnam (46%), Cambodia (49%), Bangladesh (37%)—essentially any nation that dared to offer competitive manufacturing has been slapped with punitive duties. China cops a whopping 54% when combined with previous tariffs. Even supposed allies aren't spared: the EU (20%), Japan (24%), South Korea (25%).

What's fascinating is the clear signal about which industries America considers strategic. Steel and aluminium? Protected. Automobiles? Taxed to high heaven (25%). Semiconductors? Temporarily exempt but clearly marked for “special attention” in future. It's industrial policy by sledgehammer subtle as a brick through a Swiss watch showroom window (those watches now subject to a 31% tariff, by the way).

This wholesale restructuring isn't a subtle nudge—it's a seismic shove toward a new economic reality. Countries that have for decades powered their growth through American consumption must now either bend the knee in negotiations, swallow ruinous taxes, or kiss goodbye to the world's richest consumer market. It's economic Darwinism on a global scale.

The global response: collective handwringing without collective action

The diplomatic responses have been a masterclass in predictable outrage. Every finance minister and trade representative reached for the same phrasebook: “deeply concerned,” “regrettable,” “harmful to all parties.” Brussels promises retaliation, Beijing vows countermeasures, Tokyo expresses “serious concerns” (the Japanese equivalent of table-flipping fury).

What's gallingly obvious is how unprepared everyone is despite having years of warning. The EU Commission can muster righteous indignation about “protecting our interests,” but where was this protective instinct when Trump was telegraphing these moves for the past two years? Europeans seem perpetually stunned when America puts America first, as if the last 250 years of history never happened.

China's reaction is equally tiresome—denouncing protectionism while maintaining some of the world's most protected markets is rich irony indeed. Their warning that “there are no winners in trade wars” conveniently ignores that their entire economic miracle was built on mercantilism with Chinese characteristics.

Most revealing is how quickly the world united against Washington. From traditional allies to strategic competitors, there's near-universal condemnation. Trump has accomplished what diplomats have tried and failed to do for decades: create genuine multilateral consensus. Unfortunately for globalists, it's consensus against their preferred economic order rather than for it.

Where is the imagination? Where are the bold proposals for a new economic architecture? Rather than clutching desperately at the fraying threads of the old order, why not seize this moment to envision something better, more resilient, more equitable? History teaches us that economic systems are not eternal—from mercantilism to free trade, from gold standards to fiat currencies, every system eventually evolves or collapses.

Business response: panic now, think later (if at all)

If I'm a factory owner deciding to move production to the US, it's also an opportunity to upgrade my automation and increase my profits. It won't contribute to the American job market, but it will still bring in more money to the coffers. This is precisely the kind of innovative thinking that businesses need to adopt now rather than simply lamenting the tariffs.

But no—instead we get corporate executives staring like deer in headlights, as if the tariff truck appeared out of nowhere rather than telegraphing its arrival with flashing lights and blaring horns for years. Nike's stock down 6.5%, Adidas plunging 9%—did these companies seriously have no contingency plans? Did they think “China+1” diversification strategies (spread manufacturing across Asia) would save them when the warning signs of broader protectionism were flashing red?

The fashion and footwear industry's plight are particularly illuminating. Having steadily migrated production from Japan to South Korea to China to Vietnam in search of ever-cheaper labour, they now find their entire model threatened. A factory in Vietnam facing a 46% tariff makes the labour cost advantage rather less compelling, doesn't it? Perhaps now might be the time to innovate in manufacturing rather than simply relocate it?

The luxury sector's predicament is equally telling—that $5,000 Swiss timepiece now carries a $1,500 tariff premium. Suddenly “Made in Switzerland” becomes a liability rather than an asset for the American market. The wine and spirits crowd are positively apoplectic—French vintners predicting sales drops of at least 20%, Italian producers fearing half their US business. Heaven forbid Europeans might need to develop their own domestic markets rather than relying on American consumption.

The entire situation reminds one of Britain's textile manufacturers during industrialisation—those who invested in power looms prospered; those who clung to traditional methods perished. Today's dividing line isn't steam power but automation. Companies willing to embrace advanced manufacturing and robotics will weather this storm; those hoping for a quick return to “normal” are betting on a future that no longer exists.

Parallel revolutions: rethinking everything at once

What makes our current moment unique isn't simply a trade war—it's that we're simultaneously experiencing multiple technological and economic revolutions, all interacting in complex ways. We're witnessing the last gasps of globalisation 1.0 coinciding with the early stages of the AI revolution, all while climate concerns drive a rethinking of energy and agriculture.

This convergence of revolutions creates both peril and possibility. Trump's tariffs act as a forcing function—compelling businesses to confront multiple transformative forces simultaneously rather than addressing them sequentially. No longer can we neatly separate industrial policy from digital strategy from AI governance. They're all intertwined in ways that defy traditional policy thinking.

By weaponizing tariffs, the US is essentially declaring an end to the era of compartmentalised globalisation. The old model—whereby manufacturing moved to Asia while America and Europe focused on services and technology—is being forcibly rewired. The message is clear: America intends to lead in manufacturing AND technology AND AI, all at once. It's an audacious bet on parallel supremacy.

This creates a fascinating dilemma for other nations. The EU, Japan, and South Korea face a strategic choice: double down on high-value specialisation that justifies premium pricing, or race to match America's protectionism with their own barriers. China confronts an even starker reality—their model of export-led growth targeting Western consumers may have reached its limits.

What we're witnessing is nothing less than the forced evolution of the global economic organism. Like the Cambrian explosion, we'll likely see rapid diversification of economic strategies as countries adapt to this new selective pressure. Some will develop regional trade blocs, others will pivot to domestic consumption, still others will specialise in areas immune to tariffication.

For companies, the implications are equally profound. The efficient but fragile global supply chains of the past 30 years suddenly look like a liability rather than an asset. The winners in this new paradigm will be those who embrace redundancy and resilience—sacrificing some efficiency for security. Smart firms will establish parallel supply chains, localise production where strategically necessary, and deploy automation and AI to offset higher labour costs in developed markets.

Historically, trade restrictions often sparked technological innovation—when Britain banned wool exports to protect domestic industry, it inadvertently helped spark the Industrial Revolution as manufacturers sought production efficiencies. Similarly, today's tariffs might accelerate the adoption of advanced manufacturing techniques, 3D printing, and automation—potentially bringing forward the Fourth Industrial Revolution by years.

The path forward: creative destruction or just destruction?

What separates Schumpeterian creative destruction from mere devastation is whether the disruption catalyses innovation or simply impoverishes. The uncomfortable truth is that the post-1945 trading system, for all its faults, delivered unprecedented prosperity. Dismantling it without a viable alternative risk throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater.

The most damning indictment of our current business and political leadership is not that they failed to prevent tariffs—it's that they failed to prepare for them despite ample warning. The missed opportunities are legion:

- Corporate Complacency: Rather than fundamentally rethinking supply chains during the Biden administration's trade détente, companies made superficial adjustments. Moving from China to Vietnam isn't strategic reimagining—it's geographical shuffling. The fact that Nike, Apple, et al. find themselves equally exposed now (just to different countries) reveals a profound failure of imagination and foresight.

- Policy Paralysis: Governments worldwide had years to forge new trade agreements, reform the WTO, and create more resilient economic structures. Instead, they clung desperately to a status quo that was visibly crumbling. The EU couldn't finalise deals with Mercosur or India; TPP withered without American participation; the UK-US trade agreement remains eternally “in negotiation.”

- Innovation Deficit: The interplay between tariffs and technology highlights another missed opportunity. Western nations could have leveraged their technological advantages to reinvigorate domestic manufacturing BEFORE crisis hit. Germany's Industry 4.0 and similar initiatives remained underfunded passion projects rather than national priorities. Now, when Trump demands manufacturing return home, the infrastructure, skills, and supplier networks simply don't exist at necessary scale.

The way forward requires imagination currently lacking in most boardrooms and capitals. Businesses must embrace the chaos as opportunity—using this shock to accelerate automation, rethink product design, and create new business models less dependent on global arbitrage. Governments must replace reactive outrage with proactive reinvention—building regional resilience while avoiding isolationist dead-ends.

For Europe especially, this crisis should trigger serious soul-searching. The continent's economic model—exporting high-value goods to America and China while importing energy and components—suddenly looks precarious. Without American consumers or Chinese growth, what drives European prosperity? Perhaps developing stronger intra-European markets, investing heavily in automation to offset labour cost disadvantages, or pioneering entirely new industries around sustainability and climate adaptation?

For developing nations, the calculus is equally complicated. The traditional development pathway—export manufacturing leveraging low labour costs—faces unprecedented headwinds. Countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh must now consider whether leapfrogging directly to automated production makes more sense than competing on labour costs alone.

Conclusion: adapt or perish

The Roman Empire didn't fall in a day, and neither will the post-war economic order. But Trump's tariffs may well be remembered as a watershed moment—the point where globalisation 1.0 definitively ended and something new began. What that something is, remains undetermined, dependent largely on how businesses, governments, and societies respond.

Will we see creative adaptation or reactionary retrenchment? Will parallel revolutions in industry, technology, and sustainability converge into a more resilient system, or will fragmentation lead to conflict and stagnation?

History offers contradictory lessons. The protectionist reflexes of the 1930s deepened the Great Depression and contributed to global conflict. Yet earlier waves of protectionism sometimes spurred domestic innovation and industrial development. The determining factor isn't the tariffs themselves but how societies respond to them.

For businesses, the message is clear: stop whinging and start reimagining. If Vietnam now carries a 46% tariff penalty, then automated production in higher-wage countries suddenly looks economically viable. If commodity components face tariffs, perhaps designing products that use fewer imported parts makes sense. If global supply chains are vulnerable to political whims, then perhaps shorter, more regional production networks offer better risk-adjusted returns.

For policymakers, the challenge is balancing legitimate protection of strategic industries against the prosperity that flows from open exchange. The answer isn't a simplistic embrace of free trade or protectionism, but a sophisticated blend that recognises both the value of global connections and the necessity of economic security.

What's certain is that the future will reward adaptability over rigidity. As Darwin observed, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent. It is the one most adaptable to change.” Today's economic environment has changed dramatically, seemingly overnight. Those who adapt fastest will thrive; those who cling to yesterday's assumptions will falter.

The next chapter of economic history is being written now, not by theorists or politicians, but by entrepreneurs and innovators responding to new constraints and opportunities. The parallel revolutions—industrial, digital, artificial—will continue evolving, interacting in ways we can barely predict. Our task isn't to resist this evolution but to shape it toward human flourishing rather than zero-sum conflict.

So enough with the handwringing. The tariffs are here. The old economy is ending. What are you going to build in its place?

EU politicians, and those in the UK should be shamed. There’s no excuse not to be prepared for something this bloody obvious…